Panelists – Be forthright! The <DWIcompanies .com> decision by ICA Director and Domain Name Investor, Nat Cohen:

There is often a disconnect between how UDRP decisions are reasoned and how they are written. This is particularly evident with the finding of bad faith. In making a finding about bad faith, a panelist weighs all the evidence as a whole within the context of the circumstances of the case to assess whether it meets the balance of probabilities standard. It is rare that one piece of evidence, standing alone, stripped of context, is conclusive evidence of bad faith. Yet that is how UDRP decisions are often written.

One piece of evidence will be mentioned. The panelist will then state that this is evidence of bad faith. Another piece of evidence will be mentioned. The panelist will state that this too is evidence of bad faith. The approach taken by these panelists is to list as many pieces of evidence as possible, stating that each one is evidence of bad faith. The longer the list – the panelist apparently believes – the more conclusively the panelist has supported his or her finding as to bad faith.

Yet there is a problem with this common approach to drafting decisions. It likely misrepresents the panelist’s thought process and, if so, it misleads the reader. The panelist’s task is to review and assess the facts holistically. By breaking down the evidence into individual pieces and then drawing inferences of bad faith from the fragmentary evidence devoid of the larger context, the panelist is drawing an overly broad inference as to the bad faith of the respondent from insufficient evidence – and doing so repeatedly. This produces another problem – a poor quality jurisprudence based on poorly articulated rationale. Despite the abbreviated nature of the UDRP process and the reluctance to spend a significant amount of time drafting decisions for very little compensation, if panelists generally adopt a more forthright approach articulating why they assess that the cumulative evidence as a whole meets the balance of probabilities standard, this will have a beneficial effect for UDRP jurisprudence.

In the DWIcompanies.com dispute, the evidence demonstrates that the Disputed Domain Name was registered and used in bad faith to target the Complainant, BWI Companies, Inc., a regional, wholesale distributor of an assortment of lawn, garden, and animal related products. Particularly compelling is the web page that was created at the DWIcompanies.com domain name, whichx appropriates the Complainant’s name and logo.

Further, as alleged by the Complainant, and apparently backed with adequate supporting evidence, “The disputed domain name was also used to commit several cybercrimes against Complainant, such as setting up bank accounts and credit cards. Complainant filed police reports regarding these cybercrimes and portions of the reports are submitted as an annex to the Complaint.” In addition, the Respondent committed identity theft “since Respondent used the name of a retired executive of Complainant to register the disputed domain name”.

This evidence paints a compelling picture of bad faith registration and use. It is more than sufficient to meet the balance of probabilities standard. Yet, if that is how the Panelist reasoned to make a finding of bad faith registration and use, that is not how the bad faith section is written.

Instead, the Panelist highlights five generalized concepts and draws inferences from each of these, most often based on isolated facts. Some of the inferences are overly broad. Let us look at the five reasons offered.

“First, the use of a disputed domain name to intentionally attempt to attract Internet users to a respondent’s website or online location by creating a likelihood of confusion or a false association with a complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation or endorsement of the registrant’s website or online location demonstrates registration and use in bad faith.”

Yes, as the screenshot above shows, the Respondent certainly did this.

“Second, the BWI Mark, which was used and registered by Complainant in advance of Respondent’s registration of the disputed domain name, renders it wholly implausible that Respondent created the disputed domain name independently. Moreover, where a disputed domain name is so obviously connected with a well-known name, product or service, its use by someone with no connection to the name, product or service indicates bad faith…”

No, that’s not correct as the mere registration and use of the Mark by Complainant does not, alone, create such implausibility. BWI Companies, Inc. is not a generally well-known company. The decision makes no mention of any submitted evidence that would support this conclusion such as marketing efforts, social media pages, customer testimonials, news articles, web traffic statistics, etc. It appears to be a business-to-business wholesaler that does not sell directly to consumers. I live in Washington, DC, not far outside of its region of operation, and, as best as I can recall, I had never of the Complainant before. Indeed, BWI is the airport code for, and is the name locals use to refer to, one of the major DC area airports, Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport.

Neither is it wholly implausible that someone would independently register DWIcompanies.com, without knowledge of or the intention to target a company called BWI Companies. A three-letter acronym combined with a general business term such as “companies” is viewed by domain name investors to be a non-distinctive term with possible widespread appeal, such that it is considered investment quality. For example, the domain name tmtcompanies.com is registered to a domain name investor and is currently being offered for sale – https://dan.com/buy-domain/tmtcompanies.com. Yet there is a similarly named company, CMT Companies, operating on the domain name cmtcompanies.com. According to the reasoning in this decision, it would be wholly implausible that the tmtcompanies.com domain name would be created independently of knowledge of CMT Companies, and that any use of such a domain name would indicate bad faith with respect to CMT Companies. Yet this is a baseless conclusion that is not supported by the evidence.

“Third, Respondent registered and is using the disputed domain name in bad faith as Respondent engaged in typosquatting. See Cost Plus Management Services, Inc. v. xushuaiwei, FA 1800036 (Forum Sept. 7, 2018) (“Typosquatting itself is evidence of relevant bad faith registration and use.”). Here, Respondent engaged in typosquatting by substituting the letter “d” for the letter “b” in “bwi” (resulting in “dwi”). Therefore, the Panel finds that Respondent registered and is using the disputed domain name in bad faith per Policy paragraph 4(a)(iii).”

This is a subsidiary point and is either incorrect or redundant. It is possible to substitute a “T” for a “C” in CMT” (resulting in “TMT”), as noted above, without it being typosquatting. What makes this instance typosquatting is the blatant appropriation of and targeting of the Complainant’s mark as noted in the first reason, not merely registering a domain name with a different first letter as the Panelist suggests in this third point, so this reason is subsumed within the first reason.

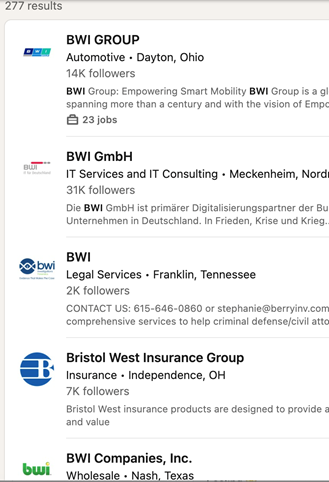

Moreover, there are hundreds of companies named “BWI” and the Complainant is not the most prominent among them:

And LinkedIn shows 400 results for companies with the name “DWI”:

Drawing the conclusion as a general inference of bad faith that someone who registered a domain name with “DWI” is typosquatting on the goodwill of one specific company out of hundreds that use the acronym “BWI” is unjustified.

“Fourth, Respondent registered and is using the disputed domain name in bad faith because Respondent made a general offer to sell the disputed domain name. A general offer for sale of a domain name incorporating the trademark of a third party can evince bad faith under Policy paragraph 4(b)(i)…”

No, on its own the general offer to sell DWIcompanies.com is not compelling evidence of bad faith with respect to BWI Companies, no more than the general offer to sell the domain name TMTcompanies.com is bad faith targeting of the company operating on CMTcompanies.com. What makes the sale offer suspect is Respondent’s other targeting activities, but the panelist doesn’t mention this and assumes that the reader will interpret the generalized statement about sales against the backdrop of the case.

“Finally, Complainant contends that Respondent has provided false contact information in connection with the registration of the disputed domain name, which in this case amounts to identity theft.”

Yes, that the name of a retired executive of the Complainant was used without authorization on the domain name registration is strong evidence of bad faith targeting of the Complainant.

In this dispute, the blatant impersonation of the Complainant’s marks, the alleged illegal activities, and the impersonation of the Complainant’s former executive were in combination compelling and sufficient evidence of bad faith.

Why didn’t the Panelist say this in so many words? Why did the Panelist find it necessary to pad the reasons for finding bad faith with other generalized reasons whose scope was far too broad, which were poorly supported, and which were unnecessary?

This Panelist is not alone in exhibiting the tendency to break down a decision into its component parts and then to draw overly broad inferences on each component, rather than to offer an assessment of the evidence as a whole. As I noted in my comment on the Hubbbell.com decision, which I faulted for “Offering unclear reasoning that is susceptible to misinterpretation”, the Panelist there took a straightforward case of cybersquatting and padded it with inaccurate citations and poor inferences, in particular “Failure to resolve to an active website is evidence of bad faith.” Perhaps the Panelist in the Hubbbell.com decision merely intended to make the point that, in his view, the domain name being passively held did not preclude a finding of bad faith given all the other circumstances in the case. But by making the point as a bare assertion stripped of context, it suggests that every domain name registrant who has an undeveloped domain name is guilty of violating the UDRP. This provides jurisprudential precedent and encouragement to any company that wishes to abuse the UDRP by making a baseless complaint against an inactive domain name.

The underlying reason for this approach to writing decisions is likely to maintain the pretense that the UDRP is based on objective criteria rather than on a subjective smell test. While a panelist may believe that the more boxes that are checked, the better the decision, such an approach degrades the quality of the decision.

The UDRP is at its root a subjective assessment of the respondent’s intentions, taking the evidence as a whole and “sniffing” it to assess whether it gives off the stench of bad faith targeting. I discuss this in a CircleID article, where I emphasize the importance of panelists educating themselves to have a more accurate “sense of smell” – read here.

For a panelist to openly acknowledge this would lead to a decision in the DWIcompanies.com dispute that would say something like – “That the Respondent openly impersonated the Complainant’s name and logo on its home page and committed identity theft in using the name of a retired Complainant executive to register the Disputed Domain Name while using a Disputed Domain Name that differed from the Complainant’s name by only one letter is in my judgment sufficient evidence to meet the balance of probabilities threshold for finding registration and use in bad faith.”

That is a straightforward explanation of the reasons for finding bad faith in one sentence. It is a holistic approach that assesses the totality of the evidence. It may faithfully express the reasoning of the Panelist.

This clear statement of the panelist’s thought process is preferable to breaking the evidence down into its component parts and assessing each one separately and as abstract principles. Worse yet, one of these overreaching principles may be cited by another panelist in a future decision and thus perpetuate the idea that these isolated facts, alone, are sufficient for a finding of bad faith.

Adopting a check-the-box list of criteria is imprecise and is often too broad so that it applies to innocently registered domain names, as with the TMTcompanies.com example above. To use an analogy, it is as if a jury said, “We find the defendant guilty of murder because he owned a gun, which is evidence of guilt (✓), knew the victim, which is evidence of guilt (✓), had a criminal record, which is evidence of guilt (✓) and was known to be violent, which is evidence of guilt (✓).” That checks a lot of boxes. Each fact in isolation is a relevant piece of evidence. Yet taken as a whole, it is far from sufficient evidence to convict the defendant of murder. Drawing inferences of guilt from each piece of evidence on its own leads to unjust results. If all juries relied on this approach, many innocent defendants would be wrongly convicted of murder. We can readily see the flaws of this approach in a murder trial. Why is it considered acceptable in a UDRP decision?

It would be far better if the jury accurately expressed why they returned a guilty verdict: “We find the defendant guilty of murder because we believe the eyewitness who saw him shoot the victim and because he was found at the scene of the crime holding the murder weapon.” This may not check as many boxes as the previous justification, but it is more compelling and relevant, and it is less likely to send innocent defendants to the electric chair.

The job of the panelist is to assess the evidence as a whole and to come to a determination. In writing the decision, share with your readers how the individual pieces of evidence, like brush strokes of different colors, came together as a whole to paint a picture in your mind.

Panelists – don’t hide behind a check-the-box approach that requires drawing overly broad inferences from individual pieces of evidence. Share your thinking! Be forthright!

About the Author: Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

Comments 1

Awesome analysis, Nat. Thank you!