SMARTCONTRACTS .COM Confusingly Similar to SMARTCON?

The Respondent is identified as “Expiry Assignment Service / Afternic, LLC – On Behalf of Domain Owner”. Afternic is GoDaddy’s aftermarket and auction business unit. This profile indicates that the disputed Domain Name’s registration expired, and it is in the post-expiration auction pipeline. According to GoDaddy, an expired domain name is removed from the registrant’s account after 72 days following expiry… continue reading

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.17), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ SMARTCONTRACTS .COM Confusingly Similar to SMARTCON? (smartcontracts .com *with commentary)

‣ Unsubstantiated Allegations and Misplaced Case Law Leads to RDNH (flyrcw .com *with commentary)

‣ Was This Good Faith Collaboration or Cybersquatting? (trimble .ai *with commentary)

‣ During the Proceedings, Complainant Requests Addition of Domain Name (miraclecashfacts .com and mtrcstock .com)

‣ Indian Court: Respondent is an “Inveterate and Habitual Cyber-squatter and Domain Name Infringer” (apsen .com *with commentary)

SMARTCONTRACTS .COM Confusingly Similar to SMARTCON?

<smartcontracts .com>

Pane list: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The Complainant owns and operates a blockchain-supported network and offers various services under the SMARTCON and SMARTCONTRACT marks. The Complainant asserts rights in the SMARTCON mark based upon registration with the USPTO (September 5, 2023). The Complainant contends that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name after it had been held by or under the control of the Complainant for at least 8 years and the Complainant omitted to renew it and that the Respondent then sought to exploit Complainant’s reputation in its SMARTCON and SMARTCONTRACT marks by offering the disputed Domain Name for sale at auction shortly after registration.

The Complainant further adds that the disputed Domain Name resolves to an inactive webpage, which as of March 13, 2024 resulted in warnings of phishing activity being provided to Internet users. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding. The Complainant’s Additional Submission consisted of two declarations made by the General Counsel of an affiliated entity of the Complainant demonstrating that as of October 14, 2014 the Domain Name was held in the name of the co-founder and CEO of the Complainant and later the disputed Domain Name was renewed by an individual employed by the Complainant on December 12, 2022 for one year. That employee left the Complainant in 2023 and the Domain Name was not renewed following his departure.

Held: The Respondent’s <smartcontracts .com> domain name is identical or confusingly similar to Complainant’s SMARTCON mark as it wholly incorporates the SMARTCON mark, adding the generic term “tracts” which results in the replacement of the “con” abbreviation with the word “contracts” and adding the “.com” generic top-level domain (“gTLD”).

The WHOIS lists “Expiry Assignment Service / Afternic, LLC – On Behalf of Domain Owner” as registrant of record. Coupled with Complainant’s unrebutted assertions as to absence of any affiliation or authorization between the parties, the Panel finds that Respondent is not commonly known by the Domain Name in accordance with Policy ¶ 4(c)(ii). The Domain Name is presently inactive which by itself does not show a bona fide offering of goods and services.

The Complainant alleges, and provides evidence supporting its allegations, that the Respondent acquired the Domain Name after the Complainant failed to renew it and then posted the domain name for sale on a public auction site for an amount well in excess of any out-of-pocket costs shortly afterwards. Such conduct is not, absent any other information, a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate noncommercial or fair use per Policy ¶¶ 4(c)(i) or (iii).

The Panel further finds, on the balance of probabilities, that the actions of the Respondent, in registering the Domain Name in or around December 2023 following the failure of the Complainant to renew the Domain Name (and then using it to take advantage of any reputation that arose from its use by the Complainant by immediately placing it up for auction) amounts to opportunistic registration which may in and of itself be considered evidence of bad faith registration and use under Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii). The Panel reaches this conclusion with some reluctance, noting that the Domain Name, while corresponding to a mark (SMARTCON) registered by the Complainant and another mark (SMARTCONTRACT) used by the Complainant, consists of two generic words (smart contracts) that together have a generic meaning.

It may have been the case that the Respondent registered and sought to sell the Domain Name for its generic meaning and did so unaware of the Complainant. However, the Respondent has chosen not to participate in this proceeding and provide any explanation of its activities and there is no other evidence before me that would enable me to reach a conclusion that supports an absence of bad faith registration on the balance of probabilities. In such circumstances, I am entitled to accept all reasonable allegations set forth in the Complaint, namely that the Respondent opportunistically registered the Domain Name, which had been held by or by associates of the Complainant for at least 8 years, in awareness of the Complainant and its reputation and sought to capitalize on this reputation by offering the Domain Name for sale. This amounts to registration and use in bad faith under Policy ¶ 4(b)(i).

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: J. Damon Ashcraft of SNELL & WILMER L.L.P, Arizona, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

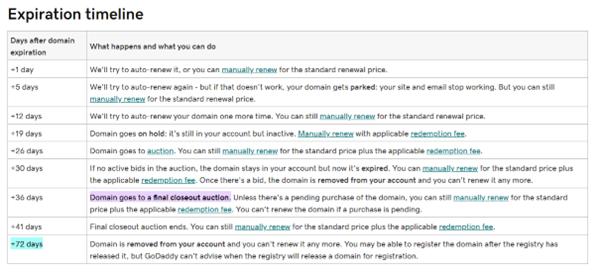

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: The Respondent is identified as “Expiry Assignment Service / Afternic, LLC – On Behalf of Domain Owner”. Afternic is GoDaddy’s aftermarket and auction business unit. This profile indicates that the disputed Domain Name’s registration expired, and it is in the post-expiration auction pipeline. According to GoDaddy, an expired domain name is removed from the registrant’s account after 72 days following expiry:

Unless the domain name already went through the auction and was in the interim period after the domain name was sold but before being transferred to the new owner, the “domain owner” is Afternic itself. In any event, the registrant was Afternic at the time that the Complaint was filed.

According to the decision and Whois records, the Domain Name’s registration expired on December 11, 2023. The Complaint was filed on March 20, 2023. That is 101 days after the expiry meaning by the time that the Complaint was brought, the original registrant was no longer able to renew it since it was beyond 72 days. According the GoDaddy post-expiration timeline set out above, the original registrant could have renewed it at any time prior to 41 days post expiration, or in this case, January 20, 2024 – two months prior to the date when the Complaint was filed. We do not know from the decision when the Complainant first realized that the Domain Name had expired but ostensibly it was after January 20, 2024. If it had been after January 20, 2024, it would mean that the Complainant not only inadvertently allowed the Domain Name to expire but also that it did not avail itself of its ability to renew the Domain Name despite its expiration in accordance with GoDaddy policy.

The expiration of the Domain Name is governed by the Registration Agreement with GoDaddy. Accordingly, the fact that Afternic removed the Domain Name from the Complainant’s account after expiration and had the right to auction it is a contractual matter:

You agree a domain name that has expired shall be subject first to a grace period of twelve (12) days, followed by the ICANN-mandated redemption grace period of thirty (30) days. During this period of time, the current domain name registrant may renew the domain name and retain registration rights.

The domain name may also be placed in a secondary market for resale through the Auctions® service.

When an expired Domain Name registration is automatically assigned to Afternic pursuant to the Registration Agreement, it can hardly be considered to be “bad faith registration” or cybersquatting by Afternic as understood by the UDRP. Indeed, this assignment was agreed to by the Complainant when it chose to use GoDaddy and agreed to GoDaddy’s terms and conditions and then failed to renew the Domain Name.

Yet if the domain name were unique and highly distinctive, such as, for example, PEPSI.COM, would the registrar still be able to auction off the expired domain name in accordance with the contract? I think the answer is definitely, “yes” – as otherwise having a trademark, particularly a highly distinctive one, would effectively purport to override a contract and ICANN’s expiration policies. Surely that cannot be the case. This does not mean, however, that any third-party can purchase such a domain name at auction in good faith. Ostensibly this latter scenario is what the Panel apparently assumed had occurred. Nevertheless, in the circumstances of this particular case, there is no evidence that the Domain Name was actually sold at auction to a third party and therefore transferring the Domain Name may have inadvertently circumvented Afternic’s contractual rights.

Now let’s get into the merits of the case. This case could have perhaps been dealt with under the first prong of the three-part test under Confusing Similarity. The Complainant had a registered trademark, but for SMARTCON, not SMART CONTRACTS. Are these respective terms “confusingly similar”? One could perhaps say that they are “similar” to some extent, but arguably not “confusingly similar” in the sense that “smart contracts” is a well-known generic term that the average consumer would recognize as such and therefore not understand it as corresponding to a trademark, let alone SMARTCON. SMARTCON can refer to anything, such as smart construction or a conference about intelligence. Indeed, the Complainant’s trademark is for inter alia, conducting educational events in the field of decentralized computing and related consulting services. Even a side-by-side comparison arguably reveals that the respective terms are sufficiently different. If the Policy applied to merely similar domains, it would say so. But the Policy expressly includes the word “confusing” and this important modifier must be taken into account.

The Panelist stated that “adding a generic term and a gTLD to a wholly incorporated mark fails to sufficiently distinguish a disputed domain name)”. This is generally true and is a well-established approach under the UDRP. The Panelist noted that the Domain Name “adds the generic term “tracts” to SMARTCON” thereby making SMARTCONTRACTS. This strikes me as an unintended application of the general principle that adding a generic term to a trademark constitutes confusing similarity. Its one thing to add something like “store” to PEPSI or adding “support” to DELL, because the addition of these generic words relate to the distinctive portion of the mark, i.e. a store for Pepsi products or support for Dell products. Moreover, the addition of generic terms such as “store” and “support” obviously do not create a new meaningful word as does SMARTCON + tracts.

If the analysis had ended with confusing similarity, then there would have been no need to explore the remaining two prongs of the test. The problem however, is that once there is a finding that the Respondent ‘registered a domain name confusingly similar to the Complainant’s mark’, it is just a short step to also finding that as a result, t the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name and that it was registered and used in bad faith. In this case, however, despite no Response, it was apparent that the Domain Name corresponded to an independent and well-known generic term and as such, the Respondent may have had a right or legitimate interest to register such a generic term domain name on a first-come-first-served basis, absent bad faith (See for example: CRS Technology Corporation v. CondeNet (Concierge.com) NAF FA0002000093547) and Target Brands, Inc. v. Eastwind Group (FA0405000267475) (Target.com), In any event, as aforesaid, it is unclear how the Respondent could have registered the Domain Name in bad faith when it became the registrant pursuant to a contract which the Complainant itself agreed to. Of course, the Panelist was never made aware of whether the Domain Name had been sold to a third party or not, the Respondent did not respond, and the listed Registrant name was possibly misleading.

To the Panel’s credit, it did express “some reluctance” with the decision, stating that “the Domain Name, while corresponding to a mark (SMARTCON) registered by Complainant and another mark (SMARTCONTRACT) used by Complainant, consists of two generic words (smart contracts) that together have a generic meaning”. The Panel further noted that “it may have been the case that Respondent registered and sought to sell the Domain Name for its generic meaning and did so unaware of Complainant” which is clearly not the case absent evidence that the Domain Name was purchased by someone after it was sold off at auction pursuant to the Registration Agreement. But in fairness and as the Panel noted, “the Respondent has chosen not to participate in this proceeding and provide any explanation of its activities and there is no other evidence before me that would enable me to reach a conclusion that supports an absence of bad faith registration on the balance of probabilities”. Clearly had the Respondent defended, it would have been able to clear this situation up and not leave the Panel in this uncertain situation. Nevertheless, it is very difficult to conceive of any reasonable evidentiary basis for concluding that the Complainant’s SMARTCON trademark was the reason for registering SMARTCONTRACTS.COM. This would necessarily mean that the reason for registering the Domain Name was to take advantage of the Complainant’s SMARTCON trademark.

Unsubstantiated Allegations and Misplaced Case Law Leads to RDNH

Central West Virginia Regional Airport Authority v. David Six, NAF Claim Number: FA2402002082771

<flyrcw .com>

Panelist: Mr. Alan L. Limbury

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a political subdivision of the State of West Virginia that owns and operates Yeager Airport through which it renders its services. The Complainant owns rights in the FLYCRW mark through registration with the USPTO and operates online through website at <yeagerairport .com>. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has not made, nor is presently making, any legitimate non-commercial use of the domain name for any purpose, rather holds the domain name passively and offers it for sale for US $25,000. The Complainant alleges that the “Respondent clearly registered the Domain Name, which is essentially identical to Complainant’s FLYCRW name and mark, in a bad faith effort to trade on Complainant’s reputation and goodwill. Respondent was indisputably aware of Complainant and its well-known mark when the Domain Name was registered, as Complainant has been using its FLYCRW mark since 2017. See Finaxa S.A. v. Spiral Matrix, 2005 UDRP LEXIS 834 (WIPO Jan. 16, 2005).” The Respondent did not file a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant must prove under Policy ¶4(a)(iii) that the <flycrw .com> domain name “has been registered and is being used in bad faith”. The critical issue in this case is whether the Respondent has been shown to have been aware of the Complainant’s mark when registering the domain name and accordingly did so in bad faith. Para 3.8.1 of WIPO Overview 3.0 states that where a respondent registers a domain name before the complainant’s trademark rights accrue, panels will not normally find bad faith on the part of the respondent. Para 3.8.3 states that nevertheless, in certain limited circumstances where the facts of the case establish that the respondent’s intent in registering the domain name was to unfairly capitalize on the complainant’s nascent (typically as yet unregistered) trademark rights, panels have been prepared to find that the respondent has acted in bad faith. The FLYCRW mark was registered on October 4, 2022. Hence the effective date upon which the Complainant acquired rights in its registered mark is the date of the application, September 7, 2021. The disputed Domain Name was registered on June 28, 2019, some two years prior to the filing of that application. Exhibit A to the Complaint is the only evidence provided by the Complainant in support of its claimed first use of the FLYCRW mark in commerce prior to the registration of the <flycrw .com> domain name.

The Complainant provides no evidence that “through long and extensive use of the mark FLYCRW in connection with its airport services since 2017”, it had acquired common law trademark rights prior to the registration of the domain name, nor that the Respondent was “indisputably aware of the Complainant and its mark when the Domain Name was registered.”

The Panel may deny relief where a complaint contains mere conclusory or unsubstantiated arguments. The Panel is not persuaded that the facts of this case establish that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant’s then unregistered trademark rights when registering the disputed Domain Name, nor that any of the exceptions set out in the WIPO Jurisprudential Overview 3.0, Para 3.8.2 have been shown to apply.

RDNH: The Complainant failed to produce any evidence in support of its conclusory and unsubstantiated arguments claiming use by the Complainant of the FLYCRW mark prior to the registration of the disputed Domain Name nor any evidence supporting any of the exceptions set out in the WIPO Overview 3.0, para 3.8.2. The lack of any such evidence has been fatal to the success of the Complaint since the Respondent could not be shown to have had the Complainant or its mark in mind when registering the domain name. The Complainant, through its Counsel, relied upon the case of Finaxa S.A. v. Spiral Matrix, WIPO Case No. D2005-1044, in which the disputed Domain Name was registered several years after registration of the complainant’s trademarks. This persuades the Panel that the Complainant, represented by Counsel, appreciated that its Complaint should fail. The Panel therefore finds that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Varun Shekhar of Babst Calland Clements & Zomnir, PC, District of Columbia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: What price should a Complainant pay for its counsel filing a clearly deficient Complaint and relying upon clearly distinguishable case law? That is the issue which arises in this case. The Complainant made unsubstantiated and conclusory allegations thereby resulting in the dismissal of the Complaint, as the Panel noted. Dismissal is of course the proper result where a Complainant files a deficient Complaint. But here the Panel went further and declared that “the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of process”. The Panel justified this finding because the Panel was persuaded that the Complainant, who was represented by counsel “appreciated that its Complaint should fail”. It is well established that where a Complainant, especially one represented by counsel, files a Complaint knowing that it was doomed to failure, that it constitutes an abuse of process and a finding of RDNH is warranted (See for example, the recent case of Music Together, LLC v. Justine Chadly, In Harmony Music, WIPO Case No. D2023-5355 (March 28, 2024). However, on what basis did the Complainant in the case at hand, know that its Complaint would fail, as the Panelist determined? It is not entirely clear. The Panelist pointed to the Complainant’s reliance on Finaxa S.A. v. Spiral Matrix, 2005 UDRP LEXIS 834 (WIPO Jan. 16, 2005) and noted that this case involved a disputed domain name that “was registered several years after the registration of the Complainant’s trademarks”. Did the Complainant’s reliance on this clearly distinguishable case indicate a disregard for the genuine import of the case? If the Complainant’s counsel is assumed to be aware of the content of a case that he himself submits and relies on, then perhaps as the Panelist found, it can be said that the Complainant knew or ought to have known that the UDRP requires pre-existing trademark rights.

On the other hand, however, in the present case, it seems equally if not more likely that Complainant’s counsel was simply unaware of the requirements to prove common law trademark rights prior to the domain name registration where a registered trademark post-dates the domain name registration. But does that get the Complainant off the hook? Not necessarily. Although a certain amount of leniency is appropriate in holding counsel to account for familiarity with the UDRP’s requirements after 25 years of its existence, perhaps there is a line when it comes to wilful blindness or disregard for the requirements of the Policy and associated case law. For example, is it OK to file a Complaint that seeks transfer of a domain name that clearly precedes any possible trademark rights held by the Complainant, and simply chalk it up to a poor Complaint and dismiss it without sanction? Or is there a point where Panelists should give no quarter when it comes to a party that disregards the Policy and established case law?

Here, perhaps a mitigating factor “in the Complainant’s favour” is that despite the Complainant failure to provide evidence of pre-trademark registration common law trademark rights as the Panelist noted, that those unproven common law rights nevertheless possibly, if not very likely, existed given the distinctive nature of the trademark. Still, do we expect Panels to draw conclusions on facts which are entirely absent from the record, based upon mere supposition or suspicion alone? Here, the Panel seems to have adopted a strict approach that rules based upon the record alone without providing the benefit of the doubt to the Complainant, even if perhaps the Panel had its own suspicions.

Was This Good Faith Collaboration or Cybersquatting?

Trimble Inc. v. Jeff Graham, NAF Claim Number: FA2403002087048

<trimble .ai>

Panelists: Mr. Paul DeCicco, Esq., Mr. Adam Taylor, Esq., and Mr. Darryl C. Wilson, Esq. (Chair)

Brief Facts: The Complainant is the owner of domestic and global registrations for the mark TRIMBLE, and related formatives, which it has continuously used since at least as early as 2002 in connection with its physical and digital products and services for diverse industries such as agriculture, construction, and geospatial and transportation logistics. The Complainant and the Respondent collaborated in business relations from 2017 until sometime in 2023. The Respondent contends that in 2017 Trimble and the Respondent, Jeff Graham, working as part of Pique Innovations Inc., began discussion about a collaboration to integrate some of Pique Innovation’s machine learning research outputs into some of Trimble’s offerings. After months of productive meetings, emails, and other correspondence Pique Innovations registered the disputed Domain Name in 2018, so that it could be used for the new business.

The Complainant initially asserted, “the Respondent is not and has never been associated or affiliated with the Complainant and the Complainant has never authorized Respondent to use the TRIMBLE trademark or any variation thereof.” The Complainant repeatedly made the above assertion in its complaint as the primary reason Respondent had no rights or legitimate interest in or to the disputed Domain Name. However, under the Additional Submissions that contradicted its earlier statement and instead indicated the parties “may” have exchanged cordial communications, and that the parties did actually sign cooperative agreements, however, none of them gave the Respondent the right to register the disputed Domain Name.

As of October 17, 2023, the disputed Domain Name redirected to the Respondent’s website at <construction .ai>. The Complainant sent a legal letter to the Respondent on November 20, 2023, to which the Respondent replied on December 20, 2023. As of February 9, 2024, the disputed Domain Name resolved to a web page which included an “Inquire to Purchase” link, which in turn led to a Sedo page offering the disputed Domain Name for sale with an asking price of US $300,000. So far as the Panel is aware, neither party ever used the domain name in connection with their ongoing joint business operations.

Held: The Respondent asserts that as a result of their business relationship, he registered the disputed Domain Name to be used with their new business endeavor. However, the Respondent does not indicate that the Complainant specifically authorized the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name. There is however conflicting evidence regarding whether the Respondent was ever authorized, licensed, or otherwise permitted to use the Complainant’s mark. Because the Respondent has provided no direct evidence to contradict the Complainant’s assertions that no authorization was granted by the Complainant to the Respondent to specifically register the disputed Domain Name, the Panel here finds that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

The Complainant asserts that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. Nevertheless, the evidence is clear that the Complainant repeatedly misstated the nature of the relationship between the parties. Although both parties ultimately acknowledged there were ongoing professional relations between them for an extended period, with some 3,000 emails passing between them according to Respondent’s uncontested assertion, the Panel finds this is not primarily a business and/or contractual dispute between two companies that is outside the scope of the UDRP as some prior panels have concluded in similar matters. Here the parties’ business relations, as asserted, are unclear regarding the interplay of their joint venture and the domain name, however, they have both filed pleadings addressing the issues as an abusive cybersquatting matter.

The Panel makes the following additional points regarding the Complainant’s submissions in these proceedings as they relate to the Complainant’s failure to evince registration in bad faith. The Complainant exhibited a general lack of veracity and candor regarding the relationship between the parties, including a lack of any evidence or detail from the Complainant in relation to its unsupported accusation of phishing, and its misrepresentation of the Respondent’s additional domain names as proof of an alleged pattern of bad faith registrations. Further, the Respondent’s actions that arguably equated to a bad faith offering of the domain name for sale only occurred after the Complainant noticed that the Respondent of the instant proceeding had ignored the Respondent’s inquiry as to the nature of what the Respondent thought must be a misunderstanding. The Panel does not consider that the Respondent’s offering of the domain name for sale in these circumstances can be said to reflect the Respondent’s state of mind when registering the domain name some five years earlier.

Accordingly, the Panel here finds that the Complainant has not shown the bad faith registration by the Respondent, and thus has not shown bad faith registration and use per Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii).

Dissent by Panelist, Mr. Paul M. DeCicco: The Respondent not only used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith but also registered the domain name in bad faith. The past relationship between the parties does nothing to suggest that the Respondent could reasonably have believed that he had any right to register the TRIMBLE trademark in a domain name. Registration and use in bad faith are virtually universally found where, as here, having no rights or legitimate interest in the domain name the respondent was aware of the Complainant’s trademark at the time of registration.

Additionally, the ability to mind read or speculate about what the Respondent may have intended at the time of registration is unnecessary since the undisputed facts following registration create a powerful inference regarding the Respondent’s primary reason for registering <trimble .ai>. Following registration, the Respondent passively held the domain name, offered the domain name for sale, and directed the domain name to various domain names and websites under the control of the Respondent. Moreover, the Respondent does not bother to suggest any particular good faith use he might have had in registering the domain name.

Since I concur with the majority regarding Policy ¶ 4(a)(i), Policy ¶ 4(ii) and Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii) regarding the Respondent’s use of the domain name but additionally find bad faith registration, I conclude that the domain name should be transferred to Complainant.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Tara K. Hawkes of Holland & Hart LLP, Colorado, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: This is a very challenging case and as we saw, there was even disagreement amongst the three-member Panel. Where there is a disagreement amongst three-member Panels, it is often a good indication that the case is uneasy to resolve under the UDRP or that it is not a clear case of cybersquatting. On the other hand, such genuine disagreements amongst Panelists is a good reminder that despite all of our efforts to make the UDRP consistent with reliable outputs for defined inputs, at the end of the day the UDRP remains subjective and prone to different perspectives amongst Panelists.

I found it interesting that the Majority found that the Respondent had no rights or legitimate interest but that the Complainant did not establish bad faith registration and use. One would think that if a Respondent has no legitimate interest or rights in a Domain Name, that naturally it likely registered and used it in bad faith one way or another. But that is not what the Panel found. The Panel found that there was no evidence that the Respondent had the Complainant’s authorization to register the Domain Name and the Respondent obviously wasn’t known by the Domain Name since it corresponded to the Complainant’s longstanding trademark.

So, if the Respondent registered it on purpose without the Complainant’s authorization and it corresponded to the Complainant’s trademark, isn’t that bad faith? Not according to the Majority of the Panel who found inter alia that “it is not inconceivable that Respondent had no detailed plan for the domain name in mind but, rather, possessed a generalized intention to use it in a good faith manner in cooperation with Complainant”. But is such a generalized intention to register it without authorization for collaboration, not bad faith? Not really, since the Respondent could have had a clear conscience and purely bona fide intention of using it with the Complainant’s subsequent blessing. But if this is so, is it not a sort of “constructive trust” in that if the Respondent’s intentions were bona fide in this manner, wouldn’t it have handed the Domain Name back when his plans never came to fruition? The Dissenting Panelist seems to share these concerns when he wrote that “the undisputed facts following registration create a powerful inference regarding Respondent’s primary reason for registering” the Domain Name, i.e. a most generous reading of the Respondent’s intentions is that he registered it ‘just in case’ the collaboration moved forward, but never intended to have any ownership right in it apart from this collaboration.

The Majority directly addressed the issue of scope as they acknowledged that the dispute involves parties with a prior business relationship that is often found to be outside of the scope of the UDRP. Yet, the Majority nevertheless decided the dispute was within the proper scope of the UDRP. What I think can be fairly said of this case, is that the circumstances may not amount to a “clear case” of cybersquatting. Yes, it may have been framed as a cybersquatting case and did not primarily sound in a business dispute as the Majority found, but if it is nevertheless not a clear-cut case, it can still be dismissed in favour of the courts.

During the Proceedings, Complainant Requests Addition of Domain Name

Genesis Teknoloji ve Bilişim Hizmetleri A.Ş v. Kacee Jackson, WIPO Case No. D2024-0432

<miraclecashfacts .com> and <mtrcstock .com>

Panelist: Mr. Andrew D. S. Lothian

Brief Facts: The first Complainant provides crypto asset services in Türkiye via a website at <miraclecash .com> (created on January 12, 2022). The first Complainant claims (but does not provide evidence) that it has achieved significant recognition in its industry. The first Complainant owns the Türkiye trademark for the device and word mark MIRACLE CASH & MORE, (registered on April 29, 2022). The second Complainant is a Portuguese entity (in Madeira Free Trade Zone) that owns a majority of the shares in a Nevada, United States company named Metaterra Corp., which trades on an Over-the-Counter (“OTC”) market under the stock symbol MTRC. The disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com> was registered on October 30, 2023. The disputed Domain Name <mtrcstock .com> was registered on February 19, 2024, i.e., after the filing of the original Complaint against the disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com>. The disputed domain names are linked by having a single source of website content. The disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com> currently redirects to a website at the disputed Domain Name <mtrcstock .com>.

The Complainants allege that following the filing of the original Complaint, the Respondent changed the Domain Name of the website associated with the disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com> to the disputed Domain Name <mtrcstock .com> in an attempt to harm the second Complainant, and to undermine the administrative proceeding. The Complainants go on to allege that the website associated with the disputed Domain Names contains unfounded and defamatory posts that aim to damage the Complainants’ reputation and prevent their commercial activities. The Respondent contends that the disputed Domain Names are being used for non-commercial and fair use purposes to support not-for-profit reporting, commentary, and criticism. They are not monetized in any way… the website associated with the disputed Domain Names puts forward “100% factual information” which seeks to demonstrate “in an educational and documented-source manner, where participants can debate or dispute the facts” that the activities performed under the MIRACLE CASH & MORE mark constitute money laundering and an investment scam.

The Respondent further contends that the disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com> primarily engages an American audience while the Complainant’s trademark is registered solely in Türkiye, and is confined in its legal protections to Turkish territory. Such territorial rights do not impact the operation of the disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com>. The disputed Domain Name <mtrcstock .com> is not trademarked anywhere. Lawful critical discussion and consumer education which does not compete with or profit from a complainant’s business falls within the scope of fair use and contradicts the assertion of bad faith. The company Metaterra Corp does not currently trade on any stock exchange, neither name is trademarked and the terms “MTRC” and “MTRCstock” are not protected by any law.

Preliminary Matters: request to join second Complainant, request to add second disputed Domain Name, consolidation of Complaints, consolidation of multiple respondents

On February 22, 2024, before the Response was filed, the Complainant sent an email to the Center in which it stated that the website associated with the disputed Domain Name was now forwarded to the domain name <mtrcstock .com>. The Complainant added that “MTRC” is the short name for Metaterra Corp, its group company in the United States. The Complainant asked if it was possible to include Metaterra Corp. as a co-Complainant, and whether <mtrcstock .com> would be transferred to it at the conclusion of the administrative proceeding. The Complainant was informed that if it wished to add said domain name and join said co-Complainant, it should file an amended Complaint, with arguments demonstrating consolidation of the Complainants, and addressing the three elements of the Policy in respect of the domain name <mtrcstock .com>.

In the present case, the Panel is content to accept the Complainant’s request to join the second Complainant to the proceedings and to add the second disputed Domain Name following the Complaint notification. The Panel is also content to consolidate the Complainants’ respective Complaints against the Respondents. It is clear to the Panel that the registration of the second disputed Domain Name occurred after the filing of the original Complaint and as a direct response to it. This seems to the Panel to bring this case within the ambit of the type of cases described in the WIPO Overview 3.0, section 4.12.2, where there appears to have been an attempt to frustrate the proceedings by the registration of a new domain name after the Complaint notification.

Held: The Panel finds the first element of the Policy has been established for the disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com>. However, as regards the domain name <mtrcstock .com>, neither of the Complainants have stated that they have a registered trademark for MTRC or MTRC STOCK. The sole submission as to the Complainants’ rights in this connection is that the term “mtrc” in the disputed Domain Name is an abbreviation of the name and stock symbol of Metaterra Corp, a company based in the United States that is majority-owned by the second Complainant. There is a dispute between the Parties as to whether the term MTRC is genuinely a stock symbol of Metaterra Corp. However, even assuming no dispute over the Complainants’ submissions on this topic, company names and stock symbols are not by themselves generally accepted as source identifiers of the kind that would give rise to unregistered trademark rights under the Policy without some other supporting evidence. In these circumstances, the first element of the Policy has not been established in respect of the second disputed Domain Name <mtrcstock .com> and the Complaint fails to that extent.

The first disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com> contains an abbreviated version of the first Complainant’s mark coupled with the word “facts”. The Panel considers that the abbreviation of a complainant’s mark in a domain name does not signal to the public that the domain name necessarily belongs to or is operated by the complainant, unless, for example, there is evidence that the complainant habitually refers to itself by that abbreviation. No such evidence has been brought forth by the Complainants here. Further, “Facts” is not a derogatory term, and is at best neutral. It does not necessarily signal to an Internet user that it will find criticism on the related website. However, it does suggest that content at the disputed Domain Name is likely to feature some form of commentary upon a complainant’s activities rather than necessarily that such complainant itself operates the domain name concerned. In all of these circumstances, the Panel considers that, based on the assessment of the facts and circumstances presented in this case, and noting the relative neutrality of the term “facts”, the first disputed Domain Name <miraclecashfacts .com> does not fall foul of the “impersonation test” outlined above.

The Panel adds for completeness that no evidence has been placed before it by the Complainant showing or tending to show that the Respondent’s criticism is not genuinely intended (bearing in mind it is not for the Panel to assess whether content is defamatory or not) or is merely a pretext for cybersquatting, commercial activity, or tarnishment. It is the view of some panels under the Policy that the impersonation test should form part of a wider inquiry into the facts and circumstances in what would amount to a more holistic test. Even if such a holistic test were to be deployed here, the Panel is satisfied that the Respondents would still prevail due to the apparent genuineness and nature of the Respondent’s criticism (in the sense of being genuinely intended (even if highly critical, or containing opinion) rather than pretextual), the noncommercial aspect of the related website, and the use of the domain name with the qualifying term “facts”.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Indian Court: Respondent is an “Inveterate and Habitual Cyber-squatter and Domain Name Infringer”

Apsen Farmacêutica S.A. v. Namase Patel, Mumbai Domains, WIPO Case No. D2024-0978

<apsen .com>

Panelist: Mr. Kaya Köklü

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a pharmaceutical company with its registered seat in Brazil. The roots of the Complainant date back to the year 1969. Besides the use as a company name, the Complainant owns some trademark registrations for APSEN, including but not limited to the Brazilian Trademark registered on April 24, 1984, for APSEN, covering protection for various pharmaceutical products as protected in class 5. The Complainant further operates its official website at <apsen .com .br>. The disputed Domain Name was registered on July 12, 2003 by an Indian Respondent. The disputed Domain Name resolves to a landing page with pay-per-click (“PPC”) links in the Portuguese language to third party websites with pharmaceutical and related products.

Held: Having reviewed the available record, the Panel finds the Complainant has established a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. The disputed Domain Name resolves to a landing page featuring PPC links in Portuguese language to products which relate to the Complainant’s field of activity. Such use cannot establish rights or legitimate interests. Further, the Panel notes that the Respondent more likely than not had the Complainant and its APSEN trademark in mind when registering the disputed Domain Name. Given the Complainant’s long-established use of the identical trademark, as well as the <apsen .com .br> domain name from which the disputed Domain Name only differs by omitting the country code Top-Level Domain “.br”, it seems that the Respondent has deliberately chosen the disputed Domain Name to target the Complainant and mislead Internet users. Consequently, the Panel is convinced that the Respondent has registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

With respect to the use of the disputed Domain Name in bad faith, the use of the disputed Domain Name to resolve to a landing page with pharmaceutical related PPC links to third party websites, in the present circumstances, is an indication that the Respondent intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its own website. Such circumstances are evidence of registration and use of the disputed Domain Name in bad faith within the meaning of paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy. Also, the Panel accepts the failure of the Respondent to submit a substantive response to the Complainant’s contentions as an additional indication for bad faith use. The Respondent further appears to have furnished incomplete or false contact details for purposes of registration of the disputed Domain Name, seeing how the courier was unable to deliver the Center’s written communication, which additionally supports a finding of bad faith. Having reviewed the record, the Panel finds the Respondent’s registration and use of the disputed Domain Name constitutes bad faith under the Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Silveiro Advogados, Brazil

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Newsletter Editor, Ankur Raheja:

The Respondent in the matter, Namase Patel from Mumbai India, has been featured in many adverse UDRP decisions previously (see <udrp.tools search results>. More recently, he was declared as an inveterate cyber squatter by an Indian Court in the matter of Adobe, Inc vs Namase Patel And Others on 29 November 2022 (Delhi High Court 2022/DHC/005253) (see here, whereby the court pronounced damages of more than Rs 2 crores (approx. USD 240k)). There, domain names such as <addobe .com> and <adobee .com> were subject to the proceedings, with catch-all enabled for emails, hosted at <above .com>. In particular, the Court held:

(v) Additionally, the plaintiff shall also be entitled to the quantum of the damages claimed in the suit of ₹ 2,00,01,000/-. These damages are intended to be deterrent in nature given the nature of activities of Defendant-1 and the fact that he stands recognized, even in foreign jurisdictions, as being an inveterate and habitual cyber-squatter and domain name infringer.